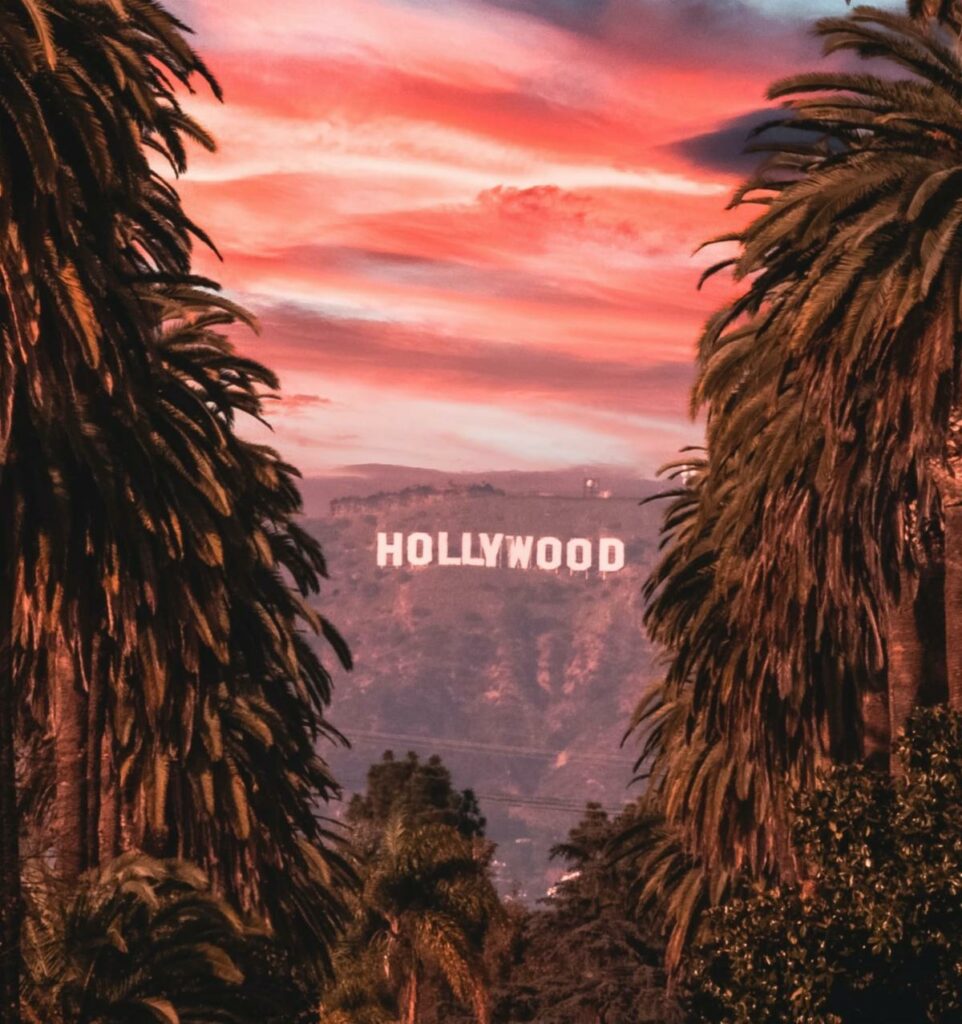

On May 3,1948, the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed an antitrust decision that completely reshaped the entertainment industry for many decades. The “Paramount Decrees” curtailed the monopolistic practices of the largest film studios at the time: Paramount Pictures, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO Pictures (The “Big Five”), and Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists (The “Little Three”). During the Golden Era of Hollywood, these studios used a horizontal distribution cartel to quash small businesses and stifle artists.

The Paramount Decrees held that the Hollywood studios must disinvest their exhibition businesses and cease anti-competitive practices such as Block Booking, Circuit Dealing, Unreasonable Exclusive Licensing, and Ticket Price Minimums (For definitions, see Page 4 of the

Court’s opinion). As a result, movie theaters became more competitive, had greater bargaining power over studios, and curated more diverse films. This was not just a boon for theater owners; artists also gained greater creative freedom and consumers enjoyed more choices. Examples of some of the most influential independent movies made possible by the Paramount Decrees include Night of the Living Dead, Easy Rider, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, Eraserhead, Dirty Dancing, Sex Lies and Videotapes, Pulp Fiction, and The Blair Witch Project.

As important as the Paramount Decrees were to the cultural and economic expansion of the movie industry, their impact and sustainability have declined over the years. Starting in the 1970s with the advent of videocassettes, home-entertainment options changed the business of theaters and studios alike. As technology went from VHS to DVD to Blu-Ray to internet streaming, theater businesses fluctuated greatly in purpose and success, studios shifted their profit sources, and artists gained new outlets to exhibit their work. Additionally, large studios today — Disney, Netflix, Amazon, and others — are not even subject to the decree’s restrictions. Lastly, the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division has changed its policies in recent years to limit consent judgment terms to a period of 10 years, rather than perpetual time frames reflected in the Paramount Decrees.

These compounding factors inevitably led to the termination of the Paramount Decrees. On August 7, 2020. U.S. District Court Judge Analisa Torres granted the Department of Justice’s motion to lift the restriction and begin a two-year sunset period where theaters can restructure their business model. In her 17-page opinion, Judge Torres noted that “the Decrees’ treatment of certain conduct as per se illegal and subject to criminal penalties — no matter what the factual circumstances — prohibits conduct that today may be deemed legal and beneficial to competition and consumers.”

The lifting of the Paramount Decrees is being harshly criticized by groups such as the National Organization of Theater Owners and the Writers Guild of America West. The majority of comments are concerned with the return of Block Booking practices, while others are worried about aggressive mergers that could again threaten independent creators and consumer choice. As pointed out by the Court, many of those concerns — while valid 72 years ago — are not wholly applicable to our modern business landscape and the decrees are not even enforceable against some of today’s biggest studios. It is plausible that a new version of the Paramount Decrees will issue in connection with potential anti-competitive practices unique to our era of streaming movies. As it stands now, however, the Paramount Decrees end quietly, especially when compared to their booming, monumental, and vital inception. Hopefully, the end of the decrees will spark new discussions around fair business practices in the modern era of entertainment.